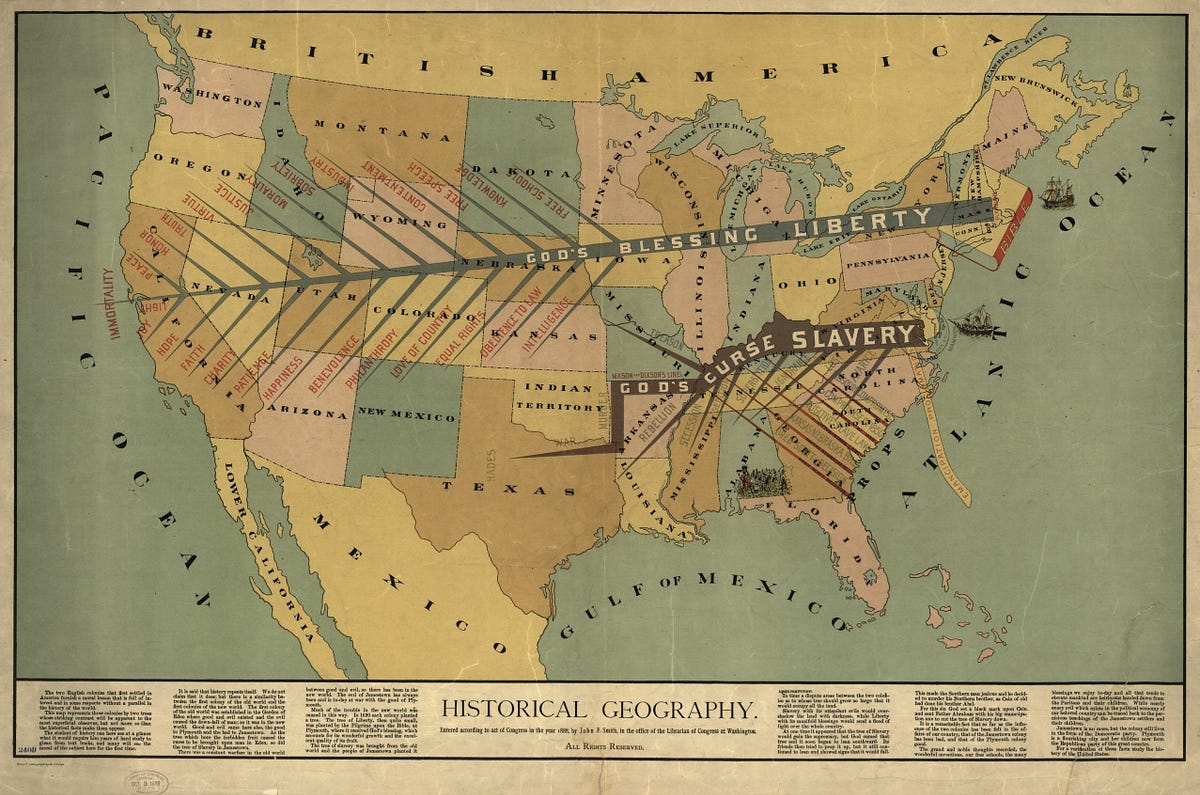

The Geography of America During the Gilded Age

In the late 19th century, the United States underwent rapid industrialization and urbanization, an era famously known as the Gilded Age. This period saw significant changes in the nation’s geography and landscape, driven by the expansion of railroads, economic development, and new discoveries of resources that fueled growth and prosperity. How did these changes influence and reflect the myriad of geographical transformations that America experienced during this economically opulent yet socially challenging time?

The first notable transformation was the expansion of the railway system. The transcontinental railroad completed in 1869 not only linked the West with the East but also dramatically altered the geography of America. Railways became the arteries of growth, enabling the transport of goods and people at an unprecedented scale. This led to the sprouting of urban hubs and peripheral boomtowns in places like Chicago, Denver, or San Francisco. Railways dictated economic corridors, town development, and even influenced architectural trends, as brick-and-mortar depots became iconic structures signalling the advent of a new urban lifestyle.

Another profound geographical shift during the Gilded Age was the exploitation of natural resources, especially in the Western half of the country. Gold and silver rushes in places like the Black Hills, California, and Nevada reshaped these regions into lucrative yet often lawless landscapes. For example, the discovery of gold at Sutter’s Mill firmly etched California into the American psyche as a land of opportunity. Beyond precious metals, the discovery and rapid extraction of oil, coal, and minerals redrew America’s energy map, with oil fields in Pennsylvania and later Texas shaping the country’s economy and landscape.

Urbanization also played a pivotal role in transforming geography. Cityscapes like New York City, where skyscrapers began to pierce the skyline, showcased the collision between old-world architecture and the modern industrial age. This vertical growth challenged the traditional horizontal expansion of towns, leading to congested urban sprawl, and subsequently, sanitation problems and stark class divisions. The period saw the emergence of slums alongside opulent districts like Manhattan’s Fifth Avenue, highlighting not just economic disparities but also the geography of social hierarchy.

Moreover, agricultural patterns saw dramatic changes with the advent of the Homestead Act of 1862, which encouraged westward migration. The transformation of the former wilderness into farmland turned the Great Plains into the "breadbasket of America." Yet, it also led to ecological disruptions, with intensive farming stripping the land of its natural vegetation, a harbinger of future Dust Bowl tragedies. Methods like sod-busting and later irrigation altered not just the economy but the physical landscape itself, creating a checkerboard pattern of fields where once native grasses dominated.

Parallel to these developments, environmental conservation gained traction, with figures like John Muir fighting for the preservation of natural lands against rampant exploitation. The establishment of Yellowstone as the world’s first National Park marked a significant shift in how Americans valued the geography of their nation, not just for its resources but as a heritage to be preserved. This shift highlighted the growing tension between industrial expansion and the need for environmental conservation.

In the industrial sectors, creators of America’s wealth amassed fortunes while altering the geography of labor. Factory towns sprouting near mills, mines, and steel industries showcased a form of urban industrialism where factories were not just places of work but often the sole providers of a community’s economic life. Waste disposal sites and pollution became geographical markers of industrial activity, pointing to a future where environmentally conscious urban planning would become crucial.

As we reflect on the geography of America in the Gilded Age, we’re reminded that this was a time when the lay of the land was radically altered by human endeavor. The physical and cultural landscapes of America were as divided as they were connected by the same forces — from the glitter of urban wealth to the starkness of resource extraction. The geography reflected an era of both unprecedented growth and simmering discontent, a testament to the complexities of progress.